Flash Loans, Mempools, and MEV

Intro

Imagine you want $1 million to perform some financial action right now. Maybe it’s profiting off an arbitrage opportunity, getting out of a bad loan, or, if you just want to watch the world burn, taking advantage of an exploit in a financial system to steal money. Obviously, you’d have to pay the $1 million back, but think about how long the process to obtain the loan in the first place would take. Plus, there’s no guarantee that your use case for the loan won’t go haywire and leave you in long-term debt.

What if there was a permissionless way to get this loan, execute whatever strategy you wanted to (so long as it can be done instantaneously), and have zero risk of going into debt because, if you fail to pay it back, it’s as if you never even got the loan in the first place. In decentralized finance (DeFi), you can with a flash loan.

What is a flash loan

Before defining what a flash loan is, let me clarify that, in this article, we will be discussing flash loans in the context of the Ethereum blockchain. The same concepts apply elsewhere, but most flash loans occur on Ethereum given the amount of DeFi activity and the broader accessibility to these loans.

To understand what flash loans are and how they work on Ethereum, we need to know a few things about how Ethereum works at a basic level. The Ethereum blockchain consists of blocks (surprise). A new block is created roughly every 13 seconds, and each block is filled with transactions (about 2,000 per block recently). A transaction could be listing an NFT for sale, swapping one token for another on a DEX, moving tokens to a layer 2 side-chain, and so on.

Further, each of these transactions can contain multiple operations, and the operations in a transaction are atomic. This means that, for a transaction containing multiple operations, they must all succeed or all fail. If even one operation fails, the entire transaction is invalidated. Think of operations inside a transaction as being “all or nothing”.

Flash loans take advantage of this atomicity by allowing users to take out large, non-collateralized loans on the condition that the loan is paid back in the same transaction (plus, depending on where the loan comes from, a small fee). If you looked into a flash loan transaction, you’d typically see it start with a large withdrawal, followed by many actions that move these tokens around to make a profit, and concluding with the repayment of the loan.

These loans can be non-collateralized because, if the user is unable to pay back the loan in the same transaction, the entire transaction is invalidated and it’s as if the loan was never given out in the first place. The user still pays the gas fees associated with the operations inside of the transaction, but, even if they took out a $100 million loan and lost it all, the loan would be invalidated. Aside from gas fees, it’s a risk-free way to access large pools of capital for a single transaction.

Since a flash loan must be taken out and paid back in the same transaction, how could they actually be useful? The most common use cases are:

- Arbitrage: Taking advantage of the same asset being priced differently in separate places. For instance, if ETH was trading for 2000 DAI on Uniswap and 2100 DAI on Sushiswap, you could use a flash loan to buy ETH on Uniswap and sell it on Sushiswap and pocket the difference after paying back the loan.

- Collateral swaps: Swapping the collateral on a loan to avoid liquidation. For instance, if you have a DeFi loan (not a flash loan!) that is collateralized by ETH and the ETH price starts dropping quickly, you could use a flash loan to swap the loan’s collateral for a stablecoin in order to avoid liquidation from the loan becoming under-collateralized and forcibly selling your collateral.

- Debt swaps: Swapping the platform or asset of a loan to obtain a better rate. For instance, if you had a loan for DAI with an interest rate of 7% but the rate for USDT loans was 5%, you could use a flash loan to pay back your DAI loan, take out a new loan for USDC at the lower rate, swap the USDC for DAI, and pay back the flash loan all in one transaction (for simplicity’s sake, I’m ignoring collateral in this example). You could think of this as instant refinancing, and you could do the same thing to switch the platform that your loan is on.

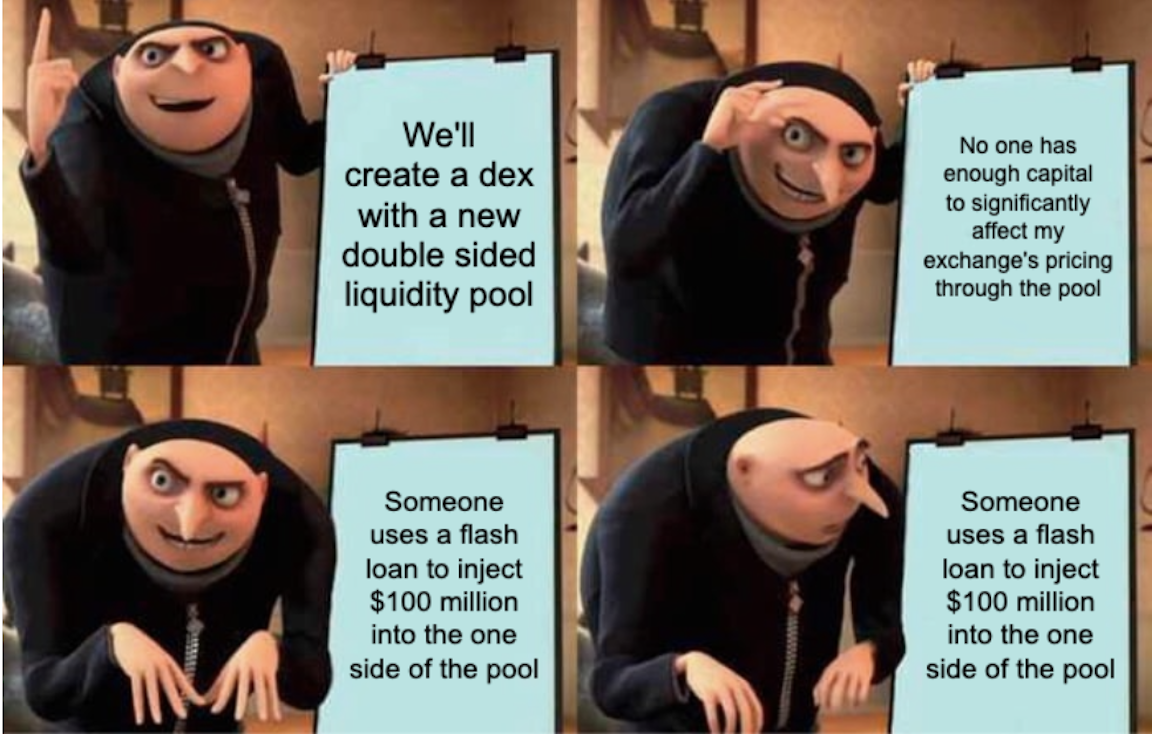

- Attacks: Flash loans are also used in attacks on DeFi platforms. Usually this involves using large amounts of capital to manipulate prices or taking advantage of systematic issues in protocols to steal tokens. Most attacks are complex, and they are requiring developers to be much more careful about protocol design and, for trading-related apps specifically, how they calculate prices.

Without oracles to assist in pricing assets, dexs can be vulnerable to price manipulation.

Anyone can get a flash loan through protocols that offer them and have sufficient reserves of capital to offer. Aave, dYdX, Uniswap, and Pancakeswap are some of the most common that offer smart contract support for flash loans. There are also some more user-friendly interfaces like Collateral Swap, Furucombo, and DeFi Saver. However, it’s easiest to understand flash loans by looking “under the hood” at the smart contracts.

Coding a flash loan

In order to obtain a flash loan, you would usually deploy your own contract. As an example, I’ve put together a short smart contract, shown below, that uses Aave1 to obtain a flash loan for 10 ether worth of DAI. If ETH was priced at $2000, we’d be getting a flash loan of about $200,000. Keep in mind that this code should not be used in production and it has not been error checked/audited. Additionally, you’d probably want to make it more customizable than this, but it’s easier to understand with things like the amount hard-coded in. Let’s walk through how the contract works - I’ll post the full contract code below, and then pull out sections to look through in more detail.

pragma solidity 0.6.12;

import "@openzeppelin/contracts/math/SafeMath.sol";

//Assuming we have the following contracts in the same directory as this contract

import { FlashLoanReceiverBase } from "./FlashLoanReceiverBase.sol";

import { ILendingPool } from "./ILendingPool.sol";

import { ILendingPoolAddressesProvider } from "./ILendingPoolAddressesProvider.sol";

contract flashLoanContract is FlashLoanReceiverBase {

using SafeMath for uint256;

//Upon contract deployment, we specify which Aave lending pool to use for the loan with the _addressProvider parameter

constructor(ILendingPoolAddressesProvider _addressProvider) FlashLoanReceiverBase(_addressProvider) public {}

//Called after we have received the loan

function executeOperation(

address[] calldata assets,

uint256[] calldata amounts,

uint256[] calldata premiums,

address initiator,

bytes calldata params

) external override returns (bool) {

//Input logic

//Could be multiple swaps, adding/removing collateral, etc.

//Check to ensure we can pay back. Even if we did not do this, Aave would revert the transaction

//Since we are only calling this with one asset, we can do some simple math

uint amountOwed = amounts[0].add(premiums[0]); //Calculate loan repayment amount

require(amountOwed <= getBalanceInternal(address(this), assets[0]); //Ensure we can repay the loan

//Send any profits wherever you want - do not keep them in this contract

//Allow the lending pool to be able to take back the amount owed for the loan

//Since we only used one asset, you could do this without a for loop, but I'll leave it as an example

for (uint i = 0; i < assets.length; i++) {

uint amountOwed = amounts[i].add(premiums[i]);

IERC20(assets[i]).approve(address(LENDING_POOL), amountOwed);

}

return true;

}

//Initiates the flash loan

function _initiateFlashLoan() internal {

address receiver = address(this);

address[] memory assets = new address[](1);

assets[0] = address(0x6b175474e89094c44da98b954eedeac495271d0f); //DAI token address

uint256[] memory amounts = new uint256[](1);

amounts[0] = 100 ether; //Specify loan amount: 100 ether worth of DAI tokens

uint256[] memory modes = new uint256[](1);

modes[0] = 0; //No debt: loan must all be paid back in the same transaction

address onBehalfOf = address(this); //Ignore for now

bytes memory params = ""; //Would need to encode if used - for instance "abi.encode(address(this), insert_params_here)"

uint16 referralCode = 0; //Ignore for now

LENDING_POOL.flashLoan(receiver, assets, amounts, modes, onBehalfOf, params, referralCode); //Communicate with lending pool to get the flash loan

}

//Called by us to initiate the flash loan

function initiateFlashLoan() public onlyOwner {

_initiateFlashLoan();

}

}

For the non-coders out there, everything following a double slash (//) is a comment, not actual code

Initially, our contract imports some Aave-related smart contracts that will allow us to interact with their lending pools to borrow DAI. When we actually deploy this contract, the constructor is called and uses Aave’s FlashLoanReceiverBase contract, which our contract inherits from, to set the lending pool to the one we want.

//Called by us to initiate the flash loan

function initiateFlashLoan() public onlyOwner {

_initiateFlashLoan();

}

When we want to initiate the flash loan, we would call this initiateFlashLoan function found at the bottom of the contract. All that this does is confirms that we, the caller, are the owner of the contract, and then calls _initiateFlashLoan to do the real work.

//Initiates the flash loan

function _initiateFlashLoan() internal {

address receiver = address(this);

address[] memory assets = new address[](1);

assets[0] = address(0x6b175474e89094c44da98b954eedeac495271d0f); //DAI token address

uint256[] memory amounts = new uint256[](1);

amounts[0] = 100 ether; //Specify loan amount: 100 ether worth of DAI tokens

uint256[] memory modes = new uint256[](1);

modes[0] = 0; //No debt: loan must all be paid back in the same transaction

address onBehalfOf = address(this); //Ignore for now

bytes memory params = ""; //Would need to encode if used - for instance "abi.encode(address(this), insert_params_here)"

uint16 referralCode = 0; //Ignore for now

LENDING_POOL.flashLoan(receiver, assets, amounts, modes, onBehalfOf, params, referralCode); //Communicate with lending pool to get the flash loan

}

Next, inside of _initiateFlashLoan, we specify that we want 100 ether worth of DAI (DAI is specified by the on-chain contract for the DAI stablecoin - it’s the 0x6b… address) and that we want mode 0 which is a flash loan. We also set some other parameters that don’t matter in this example but are required by Aave’s flashLoan function. Then, we call the flashLoan function on the Aave lending pool that we had specified at deployment time. Aave’s lending pool smart contract picks up this call, performs some logic to verify the loan, and then makes a call to our executeOperation function.

//Called after we have received the loan

function executeOperation(

address[] calldata assets,

uint256[] calldata amounts,

uint256[] calldata premiums,

address initiator,

bytes calldata params

) external override returns (bool) {

//Input logic

//Could be multiple swaps, adding/removing collateral, etc.

//Check to ensure we can pay back. Even if we did not do this, Aave would revert the transaction

//Since we are only calling this with one asset, we can do some simple math

uint amountOwed = amounts[0].add(premiums[0]); //Calculate loan repayment amount

require(amountOwed <= getBalanceInternal(address(this), assets[0]); //Ensure we can repay the loan

//Send any profits wherever you want - do not keep them in this contract

//Allow the lending pool to be able to take back the amount owed for the loan

//Since we only used one asset, you could do this without a for loop, but I'll leave it as an example

for (uint i = 0; i < assets.length; i++) {

uint amountOwed = amounts[i].add(premiums[i]);

IERC20(assets[i]).approve(address(LENDING_POOL), amountOwed);

}

return true;

}

When executeOperation is called, we know that our contract has received the flash loan. Here, we can execute the logic to perform debt swaps, arbitrage trades, or really whatever we want by calling on different external smart contracts. After that, we compare the balance we have left to the loan amount plus fees to ensure that we can afford to pay back the loan. This step is not really necessary because, if we cannot repay the loan after performing our logic, Aave knows to revert the transaction since we specified mode = 0 (no debt flash loan) in the flashLoan parameters. Regardless, I left it there as an example of how to check this. We could use a similar calculation to calculate profits and send them to ourself. Finally, we approve the lending pool to take back the amount that we owe for the loan, and Aave’s smart contract will automatically pull that amount for repayment before the transaction finalizes.

To summarize, the steps we took here were:

- Deployed a smart contract that allows us to interact with a specific Aave lending pool to obtain flash loans

- From the same account that we deployed with, called the contract’s initiateFlashLoan() function

- Specified what we wanted from Aave: a flash loan for 100 ether worth of DAI

- Received the flash loan and performed logic using the DAI we received (well, we would have if there would was actual logic in place of “Input Logic”)

- Ensured that we could pay back the loan, kept any profit, and approved the lending pool to take back that amount

Not too bad! Obviously, factors like total gas fees, slippage on trades, and price movements must be accounted for depending on what strategy you use, but you get the idea.

Let’s say you did all of this, executed a successful arbitrage strategy, and made a solid profit, but, after the block is mined, you don’t see the profit in your account or in the contract. In fact, upon further inspection, someone else performed the same arbitrage trades as you and made the profit due to their transaction being included in the block first. How could this have happened? This is known as front running, and where the Ethereum mempool and MEV come in to make things a bit more complicated. I’m not going to go too in depth on these because there is just so much to cover (especially related to MEV), but I’ll do my best to explain the general ideas.

Mempool overview

In Ethereum, the mempool is where transactions are sent prior to being added to a block. While here, transactions spread to different nodes who can view them and run checks on them. This is great for security…but it also allows for things like front running, where a node operator (well, likely a bot that is watching the mempool) could see your flash loan transaction with its profit and decide to submit the same transaction with two key differences: the operator is now the executor of the transactions, and the gas reward paid to the miner is higher. This higher gas fee incentivizes miners to place the operator’s transaction in a block before ours. In our case, the fact that our contract only allows the owner (us) to call initiateFlashLoan should protect against this, but this practice is common in cases where there is no such protection.

Quick sidenote: Depending on how you define a mempool, not all blockchains have one; for instance, Solana instead uses a transaction forwarding protocol that they call Gulf Stream2.

MEV overview

There is a connection to be made between our front running example and MEV, and I wanted to discuss it mainly because MEV is an extremely interesting aspect of blockchains that most people overlook. So, what is MEV? It stands for maximum extractable value and, in proof of work systems, is commonly referred to as miner extractable value.

Basically, it comes down to the fact that, at some point in most systems, one entity is chosen to decide the order of transactions for the current block. With this power, the entity could front run or reorder transactions themselves to maximize profit, and they could also profit from higher gas prices paid to them by mempool-monitoring bots who can pay these higher fees for inclusion of transactions that benefitted themselves. Aside from front running or reordering, there are other types of “attacks” (despite my using this word, keep in mind that not all MEV is necessarily bad) that fall under the category of MEV.

In the second scenario mentioned above where the bot pays a higher gas fee for the inclusion of certain transactions, the MEV is being split between the miner and bot operator - the miner profits from the increased gas payment, and the operator profits the difference between the transaction profit and the additional gas fee paid out. Right now, this is the scenario we see playing out most. Operators use bots to front run, back run, sandwich attack, etc. transactions, and miners collect the premium gas fees. This makes sense for now because, among other reasons, miners do not want to build a bad reputation, but this could always change.

That’s as far as I’ll get into MEV, but there’s much more to learn about the topic and lots of interesting research being done. I barely scratched the surface. Some argue that MEV is unavoidable and that the best solution we can come up with is to mitigate it and/or democratize access to it. Others view it as an existential threat to crypto that needs to be solved once and for all. There’s a lot of good discussion around this topic, and I’d encourage you to check out projects like Flashbots3,4 if you’re interested in learning more.

Conclusion

Although the mempool and MEV concepts can make things a bit more complicated, flash loans are fairly simple products that easily fit into blockchain systems. As the industry grows, it will be interesting to see how they evolve and which other new financial products come as a result of the new technology.

The risk of flash loan attacks on DeFi protocols, like I said earlier, is forcing developers to be much more careful in terms of security and much more conservative in what assumptions they can make about users’ interaction with their smart contracts. This may be a good thing for the industry overall as it will drive a higher focus on security, but there will also be successful attacks on less-secure applications that will lose people lots of money (and already have). This is why it’s important to do your own research especially when interacting with less battle-tested smart contracts.

Citations/resources

1Aave’s guide to flash loans

https://docs.aave.com/developers/guides/flash-loans

2Solana’s Gulf Stream

https://medium.com/solana-labs/gulf-stream-solanas-mempool-less-transaction-forwarding-protocol-d342e72186ad

3Flashbots article

https://medium.com/flashbots/frontrunning-the-mev-crisis-40629a613752

4Flashbots Github

https://github.com/flashbots/pm

MEV podcast with Flashbots co-founders

https://open.spotify.com/episode/3F559QFcuMezWeBOJHEvCR?si=Jv1B-oDSTSSPxDdKirDs5A&nd=1